The Dissolution of the Monasteries: James Clark (1540)

James Clark, author of Dissolution of the Monasteries

Long into the sixteenth century monasteries remained a familiar and vital part of English society. Wherever you were in the kingdom – Yorkshire, Cornwall, London, the Lakes – it was almost certain that there was a monastery just a short walk away.

And yet within a few short years in the 1530s, hundreds of these institutions vanished for good. The dissolution of the monasteries, James Clark argues in this episode, was ‘the great drama of Henry VIII’s Reformation.’ In this episode he tells us why.

*** [About our format] ***

Between 1536 and 1540 over 850 monastic institutions were shut down by the Tudor regime. This meant that thousands of monks, nuns and friars were turned out of their former homes as a monastic tradition that had flourished for a millennium came to a jolting end.

The dissolution of the monasteries, as James Clark explains, brought the most dramatic and widespread change to English society since the arrival of William the Conqueror. And yet it is often overshadowed in our view of the Tudor period today by a fixation Henry VIII’s lurid personal life.

This, however, is a distortion of the world as people knew it at the time. For hundreds of years before the events of the 1540s, monasteries had played a fundamental role in society. They were centres of faith, employment, worship, welfare, economy, culture and education.

William Weston, Grand Prior at Clerkenwell and one of the victims of the violence in 1540, as described in scene two.

In 1530, it would have been unthinkable that the monastic tradition in England could end, and yet within a decade that is exactly what had happened. As Henry VIII’s Reformation gathered pace, events began to snowball. In 1536 the First Act of Suppression was passed and the process of closing the smaller institutions began, unleashing a tide of land and wealth to the crown.

In his new book, The Dissolution of the Monasteries, James Clark, Professor of History at the University of Exeter, sets out to tell this story from a new angle, to show how people experienced the process of dissolution and the loss of their whole world. He does this by highlighting the traces of monastic life that survive in our town centres; the poignant stories in letters, the oblique references in wills.

Clark also reveals what happened to these people when the monasteries closed. Many went on to take up roles in the clergy, continuing their service of God in other ways. A small minority were executed or died in prison. Others left for Catholic countries where they could continue their calling.

For nuns there were fewer options, some found husbands and went on to have children only to find themselves being prosecuted (King Henry was not keen on former nuns marrying, unless they had taken the veil before they were twenty years old).

Meanwhile the untold wealth of the monasteries was redistributed to the crown and enthusiastically spent by Henry. This was not only a vast treasury of gold, silver and coin, but the very stones of the priories and abbeys that were used to build new coastal defences and other buildings. Many of these still surround us today.

In this episode Clark takes us back to 1540, a year at the very heart of this dramatic, contentious, violent story.

James Clark is Professor of History at the University of Exeter. He is the author of the recently published book, The Dissolution of the Monasteries: A New History (Yale).

***

Click here to order James Clark’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

*** Listen to the podcast ***

Show notes

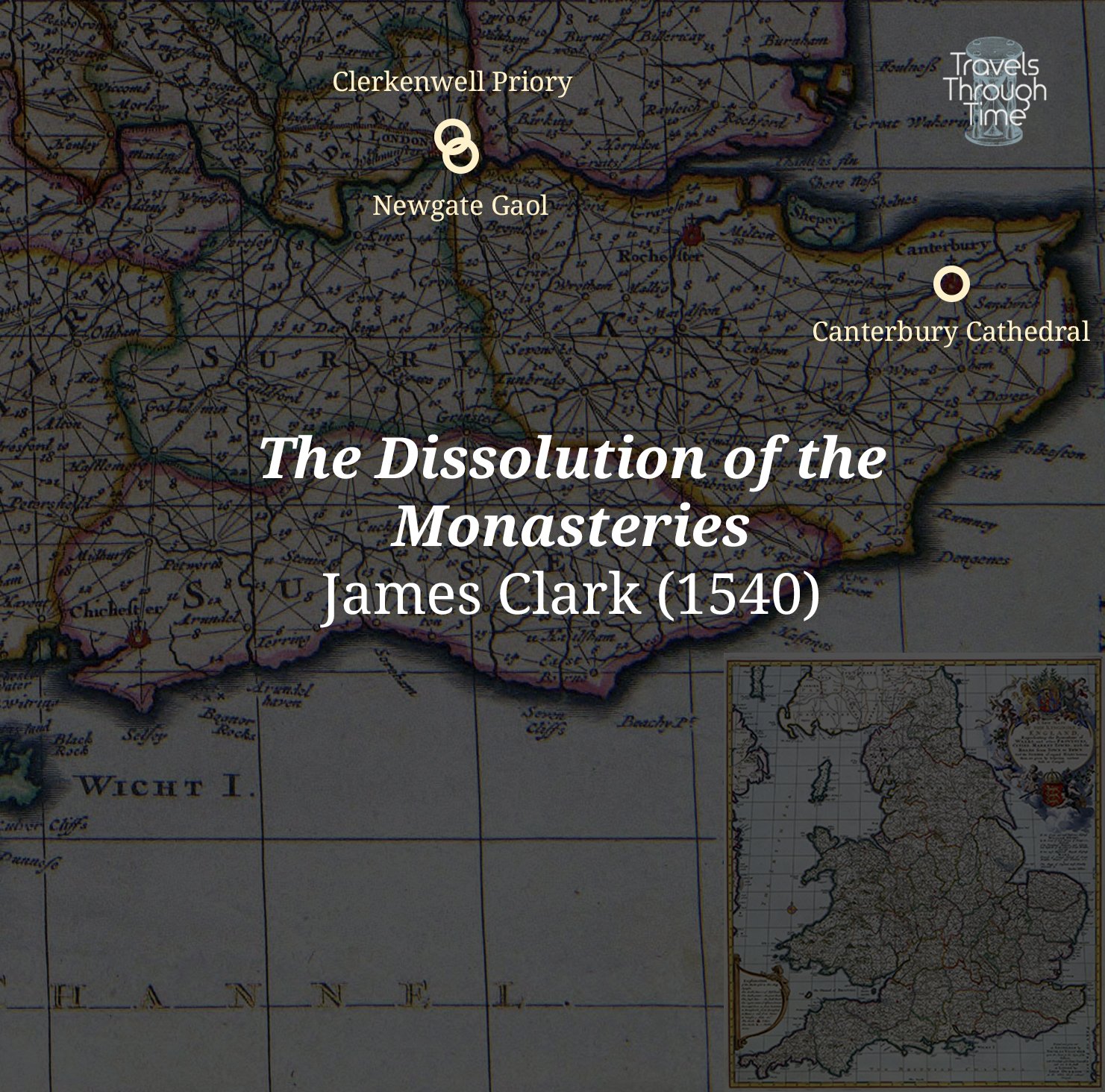

Scene One: Just before Easter, 1540. Canterbury Cathedral.

Scene Two: 7 May, 1540 Clerkenwell Priory.

Scene Three: 4 August, 1540. Newgate Gaol, London.

Memento: Epsam’s habit.

People/Social

Presenter: Violet Moller

Guest: James Clark

Production: Maria Nolan

Podcast partner: Unseen Histories

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Or on Facebook

See where 1540 fits on our Timeline

About James Clark

James Clark is Professor of History at the University of Exeter. He has published widely on medieval monasteries and their place in the medieval world and he was historical advisor on the BBC TV series Tudor Monastery Farm.

Map of the scenes

More about the scenes/memento

Scene One: Canterbury Cathedral. The last week of March, just days before Easter

Almost exactly four years after Henry VIII began a parliamentary process to close down monasteries, the final moments of the kingdom’s long history of monastic religion were witnessed here in Canterbury, the crucible of English Christianity. The monks of Canterbury Cathedral had begun the year fully expecting that they would still have a place in the Tudor monarchy’s new English church. They were so confident of their future that they planned to order a new set of habits from their tailor. The decision to dissolve even the most prestigious monasteries came suddenly in the run up to Easter. It is probably a reflection of the fact that this was policy-on-the-hoof that there is no direct documentary evidence of exactly when and how the end came at Canterbury. It seems the monks themselves were left in a strange kind of limbo, as the Crown agents waited until after the Easter holiday before they tackled all of the formalities involved in the dismantling of such an ancient institution.

Scene Two: Clerkenwell Priory (north side of Clerkenwell Road, between Faringdon and Barbican). 7 May. 1540.

Clerkenwell Priory was the headquarters of the medieval order of the Knights of St John, also known as the Knights Hospitaller. Tracing their origins to the first Crusades to capture sites in the Middle East for the Christian kingdoms of Europe, in England they had built up a wide network of houses and estates and considerable wealth. Pledged to provide military aid in the defence of European Christendom, they were quite unlike other medieval religious orders and in England they had always enjoyed the strong support of the crown and leading nobility. It was no surprise that they were the very last of all the orders to face the prospect of dissolution. As late as the spring of 1540, after all other monasteries had been closed, the Hospitallers continued to receive grants of land. But suddenly the king and his parliament caught up with this anomaly in their programme for Reformation and the order as a whole was suppressed on 7 May. It was the only moment in the Tudor Reformation when dissolution was done by act of parliament alone.

When news of the suppression reached the Grand Prior of the Order, William Weston, resident at Clerkenwell, the shock caused him to collapse, and it was said that he died before the day was out. He had been a formidable figure: already into his seventies and with a record of active service, he was the veteran soldier which Henry VIII would have wished to be. He was also a prominent public figure, and it was probably a surge of popular feeling that ensured he was buried with great panoply in a tomb which combined medieval piety with Renaissance style. Only the effigy of William now survives: a cadaver figure, designed to express the contemptus mundi (contempt for the world) of a good monk. After almost a millennium of monastic history, Prior Weston was the last man to be buried as a monk in England.

Scene Three: Newgate Gaol, London. 4 August

The Tudor chronicler, Edward Hall, describes an extraordinary scene performed at Newgate which reads as a curious coda to the story of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Hall recounts that one Thomas Epsam, a monk of Westminster Abbey, who had been languishing in the gaol – presumably for some offence related to Reformation policy, such as speaking against the king’s headship of the church – was taken out of his cell and shown to the public, condemned for his ‘malicious obstinacie’ and then stripped of his monk’s habit.

As Hall reflected, ‘this was the last Monke that was seen in his clothing in Englande’. The crown authorities had performed scenes of symbolic public theatre throughout the years of dissolution: the friar, John Forest, had been burned at a stake made from the timber taken from a popular saint’s shrine in Wales; the abbot of Glastonbury had been executed, inverted, on hill outside the town. Now, in the dog days of summer 1540, Epsam was made to remove the clothing of monasticism, to remind the subjects of Henry VIII that their king had done just that for the kingdom as a whole. By August, as many as 850 religious houses and between 10000 and 12000 monks, nuns and friars – and three times as many who earned their livings among them – saw their way of life come to an end.

Memento

Epsam’s habit: perhaps his monk’s hood, surely left in the street outside Newgate. The last tangible trace of the lived experience of monasticism in medieval England, a point-of-contact with a tradition that reached back to the very beginnings of Christianity in England and was the source of so much of its religious, cultural and social identity.

Featured images

Listen on YouTube

Complementary episodes

The Fall of Glastonbury Abbey: Richard Ovenden (1539)

The 1530s were a period of profound religious change in England as reformers sought to bring down the old Catholic structures and replace them with the new pillars of Protestantism. In doing so, they unleashed a wave of violence and destruction of epic proportions.

[Live] Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn: Prof. Diarmaid MacCulloch (1536)

In this wonderfully described episode, one of Britain’s greatest historians, Diarmaid MacCulloch, takes us back to the dramatic heart of Henry VIII’s Tudor court. The character in focus is one of the most fascinating of all: Thomas Cromwell.

Ruthlessness and Richard III: Thomas Penn (1483)

The death of the ‘charismatic but unreliable’ King Edward IV at Easter 1483 set in motion an infamous sequence of events. Within weeks Edward’s younger brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, had seized power.