Latitude: Nicholas Crane (1739)

The Enlightenment was an age of problem solving. From the tides to lightning, the movement of the planets to the workings of the human body, generations of natural philosophers sought to subdue the ancient problems of Nature.

In this episode we head back to the 1730s with the writer and adventurer Nicholas Crane, to catch sight of the very first international scientific expedition. It was French-led and it aimed to gather a precise mathematical understanding of the size of a single degree of latitude.

*** [About our format] ***

The concepts of longitude and latitude can be traced a long way back through history. When known they provide a reference point for a precise spot on the surface of the globe. This knowledge allows us to make maps, navigate oceans and to move through the skies.

At the start of the eighteenth-century, however, Western science still struggled to define these two numbers with the required precision. The story of the long struggle to calculate longitude – involving the battle between Harrison’s watches and Maskelyne’s astronomical charts – is a well-known one in the history of science. Less spoken about today, however, is the almost simultaneous struggle to define what a degree of latitude actually was.

Monsieur de la Condamine, one of the maverick heroes of the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator (WikiCommons)

The desire to tackle this problem was the catalyst for the event that Nicholas Crane calls ‘the world’s first international scientific expedition.’ This enterprise set out from France in 1735. Its destination was the mountainous, equatorial region of South America. Once there, using new tools like the quadrant, the expedition members planned to calculate just how many miles equated to one single degree.

It was this ambition that brought the French expedition, around eighty years before the fabled journeys of Alexander von Humboldt, into territory that was barely charted by Europeans. For years the team, led by the maverick figure of Charles Marie de La Condamine crossed rivers, climbed mountains, studied landscapes, the flora and the cultures that they encountered. On the way they encountered a range of phenomena that were quite unknown to the Western mind, like quinine, rubber and balsa wood,

In this episode the writer and broadcaster Nicholas Crane takes us back to 1739, a crucial year for the expedition. For years they had been struggling to achieve their objective. Shortages of money, clashes of personality and the physical danger of their surrounding had been constant difficulties.

Crane takes us high into the Andes, into an Inca site and to a moment of fatal confrontation at a local fiesta. On the way we see just how much physical danger the Enlightenment generation were prepared to risk in their pursuit of knowledge.

***

Click here to order Nicholas Crane’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

*** Listen to the podcast ***

Show notes

Scene One: April 17, 1739. peak of Sinasaguan: Four years after leaving Europe, survey is almost complete, when mountaintop camp is struck by terrible storm that smashes tents. Local helpers abandon the scientists. All seems lost. Yet the scientists persevere and descend the mountain with their observations.

Scene Two: May 20 1739. Ingapirca. During a bout of bad weather on the peak of Bueran, La Condamine seizes opportunity to ride across valley and complete first detailed survey of an Inca site. It is one of a long list of episodes that show how the scientists spread their interest beyond geodesy.

Scene Three: August 29, 1739. Cuenca. The murder in a fiesta bullring of the expedition’s surgeon. Just as the science was nearing completion, a tragedy intervenes.

Memento: La Condamine's quadrant.

People/Social

Presenter: Peter Moore

Guest: Nicholas Crane

Production: Maria Nolan

Podcast partner: Colorgraph

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Or on Facebook

See where 1739 fits on our Timeline

About Nicholas Crane

Nicholas Crane was born in Hastings, England, but grew up on the coast of Norfolk. He is an award winning writer, journalist, geographer and explorer who has presented BAFTA winning, BBC TV series Coast, Great British Journeys, Map Man and Town. His previous books include: The Making of the British Landscape, Great British Journeys, Clear Waters Rising, Two Degrees West and Mercator: The Man Who Mapped the Planet. He writes for the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian and the Sunday Times.

Map showing the location of the scenes in 1739

Background map: Library of Congress

South America Imagined

In 1735, scientists sailed from Europe to a land they could only imagine, where the equator cut through rainforest, ravine and snowy volcano. ‘Heart of the Andes’ is an imaginary view of what is now Ecuador, by the American landscape painter Frederick Edwin Church.

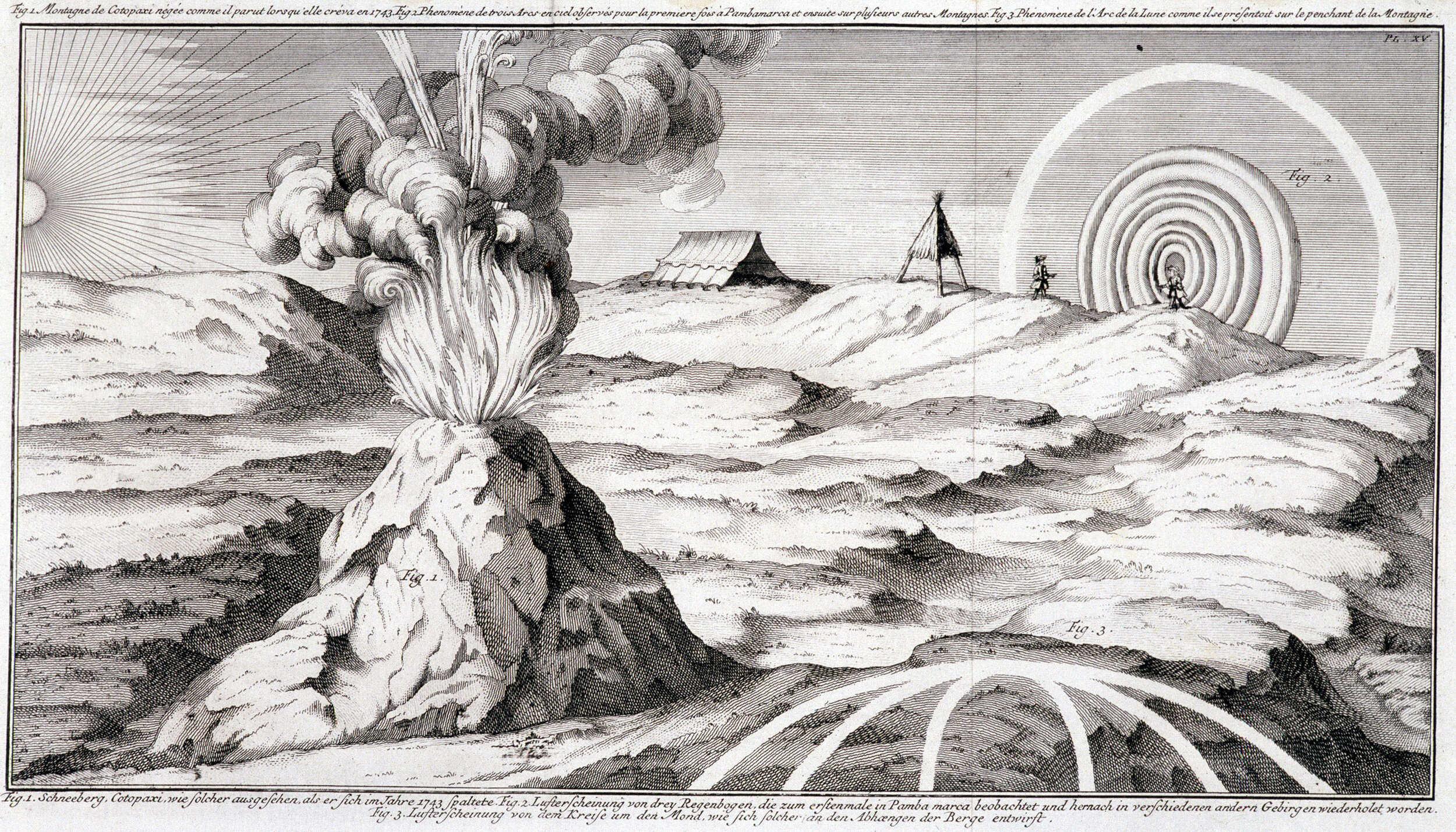

After four years of surveying, the chain of triangles extended for over three degrees of latitude at the equator, seen crossing the map, just north of Quito.

By August of 1739, the Geodesic Mission to the Equator could claim to be the world’s first multidisciplinary scientific expedition. True latitude and the shape of the Earth were about to be revealed for the first time. They had undertaken ground-breaking research on rubber and malaria. They had completed the first detailed survey of an Inca site. They had lifted the lid of Colonial corruption and the oppression of native Americans. In a mine near Quito, Ulloa had come across a strange silver-grey rock ‘of such resistance, that, when struck on an anvil of steel, it is not easy to be separated.’ The miners knew it as platina, a diminutive of the Spanish word for silver. The young lieutenant was the first European to describe platinum. Collectively the mission had drawn new maps and taken thousands of measurements, recording altitudes, locations and temperatures. They were astronomers, surveyors, geographers and botanists, cartographers and physicists, medics and archaeologists.

(Nicolas Crane, Latitude)

Listen on YouTube

Complementary episodes

Christiaan Huygens and the Dutch Golden Age: Hugh Aldersey-Williams (1655)

In the late 1640s news began to circulate the intellectual circles of Europe of the emergence of a brilliant young thinker called Christiaan Huygens. At his university in Leiden he had acquired the nickname, ‘the Dutch Archimedes’ for his skill […]

The Magical Mathematician: Prof. Simon Schaffer (1684)

On a frozen January day in 1684 three friends – Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke and Edmond Halley - met at a London coffee house to confront one of the great questions in knowledge: planetary motion. Their conversation and speculations led, in a few months, to Isaac Newton’s […]

Radicalism, madness and laughing gas: Mike Jay (1799)

In this episode of Travels Through Time the author and cultural historian Mike Jay takes us back to 1799 – a year of anxiety, action and excitement on the cusp of a new century. Although the 1790s is often overlooked, it was an extraordinary, bewildering and formative decade in European history.